Like any writer, I can look back at my previous work with no shortage of criticality. I will, however, do my best to resist any temptation to actually edit any of it. That said, I’d like to revisit A Discussion on Utopia to elaborate and clarify some of the points.

In the post, I identify three features that I believe we would generally agree a utopian society should possess. I still believe that these three features are pretty all-encompassing, but I am open to additional ideas so please contact me at pkurke@gmail.com if you have some. The three traits of utopia I discuss are:

1. Zero crime

2. Zero poverty

3. Continual progression towards (a) human happiness and (b) understanding the universe

Zero Crime

On the issue of zero crime, first we need to define “crime.” Since civilization has always had substantive gray space between “right” and “wrong,” a certain action could be a crime or not depending on the presiding legal authority who acknowledges and judges the action. We likely evolved our senses of right and wrong. An action is righteous if the actor had pro-social motives, in other words, he was doing something for the good of the tribe. Likewise, a wrongful action feels that way because we suspect that the actor had the intention of benefitting himself or herself at the expense of the tribe. It’s hard to fathom everybody agreeing on right or wrong: one American may feel that a young lady who had an abortion is a criminal, another American may feel that an overpaid CEO is a criminal.

Libertarians are among the only group that have a clear underlying axiom defining right and wrong. The non-aggression principle (NAP) is an ethical principle forbidding any aggressive or coercive act. From this perspective, a woman who pays a man for a sexual act is completely righteous, because they both agreed on the transaction and no coercion has taken place. The exchange was voluntary, and we assume that if it was not beneficial to both parties, they will not agree to do it again. Any aggressive act that transpired is a crime in and of itself, unrelated to the act of prostitution. The exchange of sex for money is illegal in the United States because voters have elected government officials, and the majority of them agree that prostitution is wrong under all circumstances. For contrast, die-hard libertarians maintain that taxation is a violation of NAP, since a taxpayer is being coerced into the transaction. For a lot of folks, achieving a perfect society seems like it would be pretty hard to do without tax.

The point is that we would need to agree on a single definition of right and wrong if we want to have zero crime; only then we can discuss “how.” In the earlier post, I single out three methods of getting to zero crime. This is not intended to be an exhaustive list of ways to achieve zero crime, but it is everything that I can imagine. I have elaborated by adding pros and cons.

1. We could possibly achieve zero crime via some sort of enlightenment that makes people not want to commit crime. It’s easiest to imagine this enlightenment taking the form of a philosophy like Buddhism, but that is certainly not the only option. Perhaps it could be a materialistic enlightenment, e.g. an understanding that altruism, prosocial behavior, and honest business interactions enhance ones own power.

a) pro – positive reinforcement

b) con – may be difficult for there to be no dissension or discord against the “enlightened ones.”

2. We could possibly achieve zero crime via some sort of fear of God or eternal damnation that scares people into behaving prosaically.

a) pro – probably effective for believers

b) con – negative reinforcement, unlikely that everyone will believe, and it seems counter to progress (Most folks might not call such a society utopia.)

3. We could possibly achieve zero crime via some sort of perfect justice system that can adequately assess and analyze all relevant information surrounding every questionable action. Judgment would ensue and the efficiency of the system would deter crime.

a) pro – doesn’t require universal dogmatic beliefs

b) con – negative reinforcement, and any such system is likely to be hackable and compromising of personal privacy, because it would likely involve ubiquitous survelliance

Zero Poverty

In the earlier post, I (more or less) concluded that zero poverty is actually a question of how much equality or inequality society is willing to tolerate.

A society will tolerate inequality so long as (a) the “have-nots” lack the power to overthrow the system, (b) the “haves” don’t feel guilt over the living conditions “have-nots” and (c) the inequality is not believed to be an overall detriment to the system, i.e. it’s generally understood that the “have-nots” would wreak more havoc on society if they receive entitlements.

A society will tolerate equality until they feel that meritocracy no longer exists in any form. Perhaps utopia might adequately achieve meritocracy by rewarding those who contribute to society with something non material, but I believe it’s likely that we will always retain sensitivity in this realm.

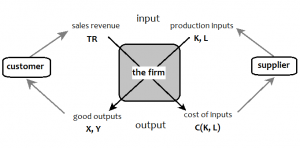

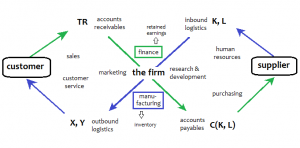

We make mental calculations of ourselves and those around us, and it looks like this: contribution divided by compensation. This idea is known as equity theory. I like equity theory because I’m a fan of the IPO model and the two are similar and compatible. I agree that we feel contempt and injustice when we think that we are being stiffed, but I do not think that we work harder when we think we are overpaid or underworked (at least not in modern society). Instead, we just construct mental models of “the ways of the world” to justify our gratuitous compensation. These mental equations and models are often fallacious.

Benoit Mandelbrot wrote the paper

How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension. The interesting mental experiment concludes that a coast’s length increases as the length of your measuring tool decreases. A gigantic measuring stick ignores all of the intimate and wandering curves of a coastline, while a smaller measuring stick will capture more of those curves and thus measure the coastline as longer.

I think the coastline question is a great metaphor to describe the fallacy of our assessments of other people’s contributions and compensations. We know our own job and our own compensation quite intimately, so the measuring stick we use is quite small. It’s capable of measuring every complication that occurs when doing our job, and respects (or over-glorifies) our job’s complexity. The measuring stick we use for other people’s jobs can be much bigger. We don’t know all the little complications that come up on their job, so we measure with a big stick: “all he does is create reports for the blah blah.” Tragically, we may even have an egocentric view of that person’s role, acknowledging only the one thing that person can do for us in our role: “I don’t know why she hasn’t emailed me back yet. All she needs to do is tell me the blah.”

It could very well be that our human nature will keep us married to some form of meritocracy in which some people will feel cheated. The degree to which the cheated ones are living abjectly is naturally limited by the stability of the society and its cultural views on meritocracy.

Continual Progression

The more I ponder the notion of continual

social progress the more I see it as being central to utopia. I think it’s important to identify what we are progressing towards; surely we don’t want to achieve equality for the sake of equality, industriousness for the sake of industriousness, or wealth for the sake of wealth. If we’re not seeking to maximize human contentment in some way, then progression is in vain.

The previous post additionally mentions progressing towards a more complete understanding of the universe. By this, I’m referring to our continual quest to uncover the laws of the physical, life, and social sciences, the humanities and the arts. I’m making the assumption that this understanding of the universe is what’s behind advancements in medicine, engineering, socioeconomic systems, and entertainment, and that those advancements are what’s behind human contentment and achievement. It follows that in order to get to utopia, the conditions need to be present to allow for as much creativity and innovation as possible.

The conclusion in my previous post was that there must be some sort of reward system (i.e. meritocracy again) in order for citizens of utopia to have the incentive to innovate. If Utopians are capable of innovating without any incentive like recognition or a financial reward, then humanity has successfully indoctrinated utilitarianism, which might be a slippery slope. Utilitarians may invent great things to help society progress, but they may also chose to do weird things like sacrifice a healthy person to harvest his organs if doing so could save the lives of two or more other people.

Conclusion

I wanted to revisit this discussion to elaborate and rationalize some of the criteria for utopia. In order to achieve zero crime, we must first agree on a definition of crime and then either build a perfect justice system, achieve some sort of enlightment, or both. The justice system runs the risk of compromising privacy. The enlightenment could either be spiritual or materialistic. In order to achieve zero poverty, we need to find the perfect balance: enough meritocracy to elicit advancement, but enough equality to not tear us apart. Finally, we should constantly be seeking to expand our understanding of reality and maximize human contentment, which also necessitates some form of meritocracy.

As I stated in the earlier post, it is extremely important to discuss utopia, and I wish our leaders would do so. Imagine two architects teaming up to build a single structure, but one has blueprints for a factory and the other has blueprints for a hotel. We need to argue about what utopia should look like first, and then we can discuss policy in the context of getting there.

Special thanks to D. Tinch for the help!