In a deviation from the typical subject matter on this blog, I’d like to discuss a philosophical matter of importance to me. It is the notion of a universal set of rules that unify all of academia. This discussion will be very short considering its scope, because that’s the way I think it should be; the connections I make should speak for themselves without over explanation.

First, a confession: before I narrowed my area of study to business, I was fascinated with the idea of a “theory of everything” (TOE), and not just a TOE unifying gravity with the weak, strong, and electromagnetic forces, but a TOE that unifies all disciplines, from the natural sciences to the humanities and beyond.

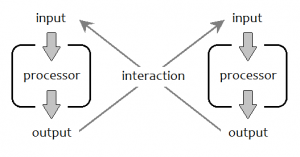

That was when I came to favor the IPO model as a substantial archetype for every system in the universe. This seldom referenced little idea is actually quite elegant. It defines a system as having input, a processor, output, and sometimes physical storge is mentioned as a 4th component.

Example 1: A squirrel detects a nut and consumes it:

input = Molecules emanating from the nut reach the squirrel’s nose, an organ refined by natural selection to input trace amounts of nutricious stray molecules for processing.

processor = Nerves analyze the shape and variety of the molecules, and activate neurons in the brain. A rush of dopamine prioritizes the pursuit of the nut and triggers a cocktail of instinctual and learned reactions (the mix of this cocktail varies depending on the species).

output = The squirrel moves, beginning a calculated search for the source of the smell.

input = The nut comes into sight.

processor = A huge shot of dopamine surges to the brain which coordinates the visual input of the nut with muscles on the squirrel’s body.

output = The squirrel moves directly towards it.

input = The nut physically enters the squirrel’s body.

processor = The squirrel’s digestive system physically processes the nut.

output = Some of the resources from the nut will be stored for energy later, and some will be physical output in the form of fecal matter.

Example 2: A company under normal operation (discussed here in more detail and relation to proprietism)

input = sales revenue, money from customers

processor = allocation of money by the finance department or top managers to raw materials, budgets, wages and salaries, equipment, interest, or savings

output = money out to vendors

input = raw materials, equipment (those two are traditionally called “capital”), and labor, back from the vendors in exchange for the money

processor = the combination of the input materials into the manufacture of the actual product, with excess saved as inventory

output = the end-product, which could be a good or service, to the customer

input = money back from the customers in exchange of the product

Example 3: Water that comes into contact with chlorine gas (sticking to what I know)

input = chlorine gas (Cl2)

processor = the physical properties of the water (H2O) are the processor, and 1 hydrogen, 1 oxygen and 1 chlorine are gained/retained as a result of this interaction, (typically with chemicals we call it a “reaction”) effectively turning the water in hypochlorus acid (HOCl)

output = 1 hydrogen and 1 chlorine, the output is hydrochloric acid (HCl)

Admittedly there is a difference with the 3rd example of a chemical reaction in that “new” state of the system (H2O) has been so physically altered by the reaction, that it is difficult to even recognize it as the same system, as it is now HOCl. The reason for this stark contrast is that the storage and processor are more easily seperable in the first two examples: a squirrel’s brain and digestive system are clearly processors, while a squirrel’s fat deposits are clearly storage. Similarly, top management at a company is clearly the processor, seperate from the physical company consisting of land, buildings, furniture, people, raw materials, and equipment. A particle or chemical reaction blurs this distinction because the physical properties of these types of systems are themselves the processors, and the interaction left the system physically altered. Upon interacting with chlorine, the water molecule lost some atoms and gained others, and became hypochlorus acid.

Technically, the company and the squirrel were physically altered by the interactions they had as well, just on a less devastating scale. The company learns and changes, if even only slightly, after every business interaction (typically in business we call an interaction a “transaction”) it has. The squirrel too was chemically different after consuming the nut, perhaps her brain even changed to remember the spot where the nut was found for future reference.

The distinction between the first two examples and the third seems even less severe if we introduced a fourth example of an extremely simple life form like a worm detecting a food source. Rather than getting a dopamine rush like the squirrel, the detection of food physically triggers a complex chemical process within the worm, causing its body to physically contract and writhe towards the food. In this example, the worm’s physical layout is a complex orchestra of physical and chemical reactions, so once again, the processor and the system itself are one in the same. We may, in an effort to relate to simple life forms, personify them by saying things like “look, it wants the food,” but no emotions such as desire are actually present. The simple organism is merely a complicated arrangement of chemical reactions that, over time, proved themselves useful to the organism’s genes.

I claim that the IPO model is an ideal scheme upon which to build science of metaphysics, because of its versaility and the way it can define most real and abstract systems. In Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics That Will Be Able to Present Itself as a Science, Immanuel Kant lays the groundwork for what metaphysics must necessarily do. The IPO model meets Kant’s criteria of being a priori, which means that it is true independent of experience. Any system must necessarily have a processor that analyzes or transforms physical objects or information and reacts to that input in the form of output. Even math is technically an abstract form of the IPO model: if we consider y=f(x), x is the input, the function “f of” is the processor, and y is the output. Defining all systems in the universe as IPO models is not a tautology, because a system is seldom explicitly defined exactly as having only those three characteristics.

Next, it’s important to discuss that IPO systems in an environment interact with each other. When they do so, the output of one system becomes the input of the next. For example, the squirrel pursuing the nut is interacting with the physical objects around it such as trees and dirt, as well as the molecules emanating from objects which she perceives as odor, and the photons from the sun bouncing off of all objects around the squirrel which she perceives through her eyes. IPO systems are in constant interaction with their entire physical environment.

Interaction is important, because it is what leads to emergent behavior. Complexity theory defines emergence as when a system starts to exhibit behavior and patterns not present in the subsystems or components alone. This is related to the concept of synergy, in which the behavior of the whole is greater than the sum of the behavior of the parts. When emergence occurs, we can say that the component IPO systems are interacting in such a way that they can be identified as a new, higher “system.” Examples would include atoms interacting to create a chemical with it’s own unique properties, chemicals interacting to create an autocatalytic system (like a virus, which can create more copies of itself), other autocatalytic systems working in concert to create complex organisms, complex organisms interacting to create swarms, people interacting to create economies, cultures interacting to create nations, etc.

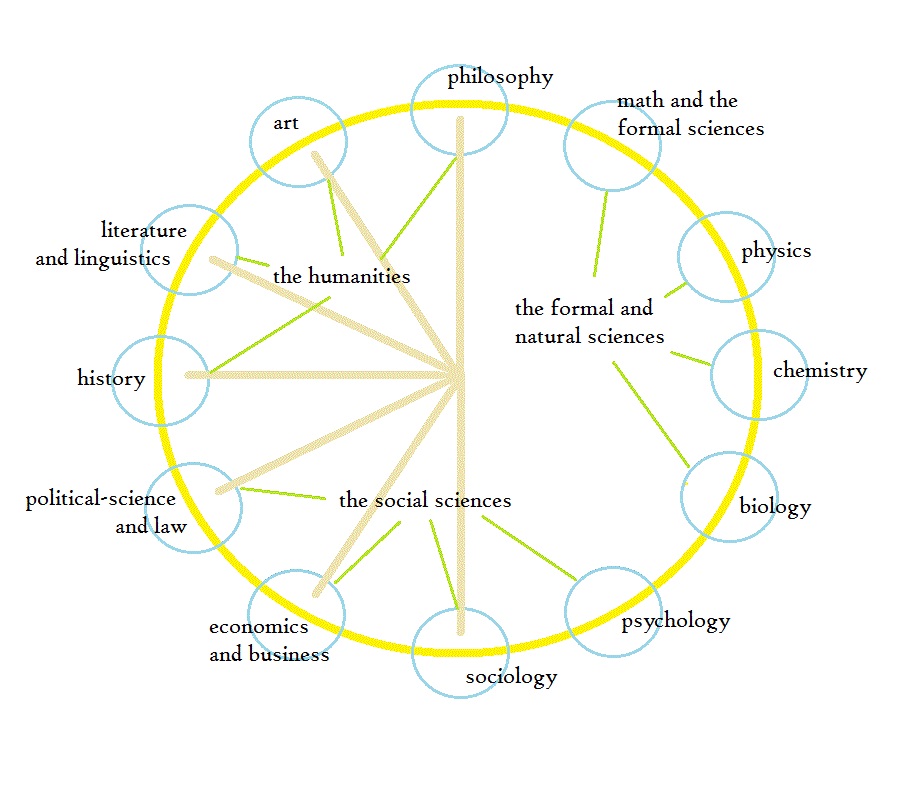

A future metaphysics could further identify those properties that are present within the component systems’ processors when the group suddenly takes on emergent behavior and creates a higher system. This exploration could be one of computer science, mathematics, complexity theory, chaos theory, information theory, cybernetics, or some other interdisciplinary study. It would need to identify what critical number of systems or ratios of system’s processing powers in relation to one another need to be present in order for the interacting group of systems to spontaneously exhibit unique patterns of behvior, enough to be able to label the group of systems as a system itself. Once we establish rules for emergence, we could unify all fields of study as being unique explorations into various major IPO models.

Math/The Formal Sciences:

The formal sciences include applied math like linear programming and dynamic systems, pure math like algebra and number theory, computer science, logic, statistics, systems science, and others. As stated earlier, the IPO model is represented in the formal sciences in the most pure sense: y=f(x), or output=processor(input). Math is the pure attempt to account for the physical universe in which we live. It does not deal with real objects in our universe; it is an abstract answer to the question “what is reality?”

Physics:

Physics is the direct application of mathematics to the real world. It deals with the behavior of physical objects as small as quarks and as large as galaxies. The processors of the systems studied in physics are the physical systems themselves, much like the chemical reaction example from above. Their physical properties interact with the physical properties of other systems, and we study these interactions through experimentation and observation. These analyses have resulted in the discoveries of strong force, weak force, electromagnetic force, gravity, static, friction, and others. Like math, physics seeks to answer the question “what is reality?” but deals with real objects, or at least objects believed to be theoretically real. When the elementary particles studied in physics form atoms, a new set of interaction rules emerges. Physics is a natural science that includes astronomy, particle physics, thermodynamics, astrophysics, geophysics, mechanics, and others, including a whole multitude of different types of physical engineering.

Chemistry:

Chemistry is the study of how atoms, groups of atoms, and mixtures of atoms interact with one another to create chemicals and materials. Since one of the initial examples of an IPO model was a chemical reaction, I only need to reiterate that the physical properties of the atoms themselves are the processors. There again have been extensive studies of these interactions in the form of experimentation and observation, and the analyses have resulted in a unique set of interaction rules which can be predicted with stoichiometry, while the periodic table of the elements serves as a near perfect map of atoms and their properties. When certain chemical compounds interact in such a way as to create autocatalytic reactions, a rudimentary precursor to life commences. Chemistry is a natural science that includes organic chemistry, cosmochemistry, synthetic chemistry, pharmacology, green chemistry, hydrogenation, and others.

Biology:

Biology is the study of living systems, their internal chemistry and their external reactions with one another. This covers the entire web of life from the simple organisms to the most complex environments. The most simple of life form may be a living system with a hard-wired processor, like the worm discussed earlier. It receives some sort of information input, in other words it detects stray molecules, sound waves, or photons, and the sensory input triggers a physical reaction in the organism. Contrast this to organisms with more complex processors that are capable of overriding instinct. For example, a dog’s instinct may tell him to lunge at the food in your hand, but when you pull it away, he overrides this urge. Upon receiving the food after waiting patiently for it, the dog’s processor remembers and overwrites the desire to lunge for the food with a new rule: when owner guy is holding food, hold still and watch him and he will give it to you. Biology is a natural science that includes anatomy, cell biology, zoology, ecology, marine biology, neuroscience, physiology, virology, and others.

Psychology:

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, a Russian physiologist by the name of Ivan Pavlov experimentally proved that very rewriting of the processor discussed above. The classic study involved conditioning dogs by ringing a bell everytime they are fed, and the result was that the dogs soon anticipated the food upon hearing the bell ring, as measured by the amount of saliva the dogs produced. Psychology is the study of that giant processor behind our eyes, it’s memory, and how it processes sensory input, which is why it is inherently dependent on biology. Remember that sensory input can be information from the outside world, something physical, or just the mere act of receiving symbolic information from another being, like hearing your friend say that they baked cookies. In the realm of psychologicy, we have crossed over from the natural sciences to the social sciences. Psychology includes social psychology, environmental psychology, evolutionary psychology, experimental psychology, sport psychology, biological psychology, clinical neuropsychology, and others.

Sociology:

Sociology is the extensive study of the interactions of groups of humans, and how their processors perceive the world in in relation to each other. In other words, we are still just dealing with IPO systems interacting with each other, only these IPO systems have the sophisticated adaptive processors that are studied extensively in psychology. Sociology is a very diverse social science including social policy, criminology, collective behavior, organizational studies, social change, gender and sexuality studies, cultural and ethnic studies, and others. Anthropology and archeology are traditionally considered social sciences and are certainly related to sociology, but there is also a strong argument to be made that they are related to history.

Sociology is important because it will represent the exact halfway mark on the chart of academic disciplines we are forming. Also, from the systems studied in physics onward, each academic discipline represented a rough chronology of the order in which systems in the universe were created. For example, particles created chemicals, chemicals created organisms, organisms evolved complex processors, then organisms with complex processors interacted with each other to create groups. Sociology is examing groups of humans, and every discipline after sociology will still be studying groups of humans. The chronology breaks down at sociology, so each additional discipline we review moving forward will not necessarily represent the chronological order in which humans achieved or invented these institutions. For example, art did not necessarily come after written language and the emergence of a rudimentary government, rather these are all human institutions that began emerging somewhat simultaneously after the dawn of civilization.

Economics/Business:

Economics, and its important sub-fields, study groups of humans in an organized exchange of resources. These are important resources that humans need as physical or informational inputs. Economics studies these interactions from the most basic, such as simple bartering or game-theory interactions, to the most complex, such as the entire global economic structure. It is tasked with trying to discern what is the most optimal arrangement for economic transactions. Economics is a social science including microeconomics, macroeconomics, international economics, socioeconomics, as well as professional disciplines like business administration, information systems, accounting, finance, and others.

Political-Science/Law:

Some sort of government or head of state seems to inevitably emerge, perhaps out of necesity, once an economic area is defined. A head of state declares laws within a sovereign area and leads the people of that area against conflicts with other rival areas. The intended purpose of the government is to ensure that the economy of the area is running optimally, though we know from history that men of power may not always live up to that function. To translate this into the language of the IPO model, the government becomes the processor of the economy. That could mean reacting to foreign inputs, or managing the internal functions of the economy, or allocating resources as necessary. Political-science is a social science that includes civics, geopolitics, policy studies, public administration, social choice theory, and all fields pertaining to geography and law.

History:

Now we transition from the social sciences to the humanities. History is the study of past events, as recorded by scribes. It tells the story of peoples, heads of states, and cultures, and their interactions over time. Just like the concept central to psychology of a processor with a memory, history is kind of like a nation’s memory. It’s like a repository of a peoples’ past interactions, and it is there, like a memory, to remind us when we should override our instinctual reactions. History is part of the humanities, and it includes world history, and all different area studies of history pertaining to nations, cultures, or regions. As mentioned previously, the highly important fields of anthropology and archeology are related to sociology, but also fit well as disciplines within history.

Literature:

Literature goes a step deeper than history as the people’s repository by capturing narratives and works of fiction. Poetry and prose are snippets of accurate or contrived interactions between humans, and together they collectively tell the human experience. In terms of the IPO model, think of a story as an information input that tells the story of another interaction. For example, The Butter Battle Book by Dr. Suess teaches us that ideological wars in which we engage are petty and wasteful. Whereas Pavlov’s dogs had to actually experience the ringing of bells and food to create the correlation in their brains, The Butter Battle Book has the power to bestow wisdom upon its readers without them having to experience a cold war. To study literature is to seek an answer to the question “what is reality?” by analyzing the human experience. Literature is of the humanities, and it includes poetry, comparative literature, creative writing, literary theory, journalism, screenwriting, and others. I think it is arguable that linguistics is a sub-field, albeit a massive one, of literature.

Art:

Art, like math, is a purely abstract attempt to answer the question “what is reality?” Instead of accounting for the universe directly with abstract models, art is more of a reflection upon the universe. To use Kant’s terminology, math, the formal sciences, and the natural sciences take a rational approach to defining our reality, whereas art and the humanities are empirical, or based on experience. Art is an artist’s reflection on reality designed to invoke a certain emotion or experience in another person. In the terminology of the IPO model, art is an informational input that gets processed a certain way, giving the viewer or patron of the art a certain hint at reality. Like Pablo Picasso so famously said “art is a lie that makes us realize the truth.” Art may include music, dance, film, theater, visual arts, applied arts, and others. Art is of the humanities.

Philosophy:

Philosophy is the ultimate major discipline, and the connector from art to math. We could say that art is a pure and abstract reflection upon reality, math is a pure and abstract accounting system for reality, and philosophy is an abstract reflection upon accounts of reality. Closely tried into the concept of philosophy is religion, which I tentatively suggest could be a sort of abstract attempt to account for reflections made upon reality. Philosophy is both empirical like the humanities, and rational like the formal and natural sciences. If philosophy seems precarious as the connector between art and math, consider how art is a commentary on the nature of existence, and math is a numerical manifestation of logic. Philosophy is regarded as a humanity, and it includes ethics, epistemology, ontology, logic, social philosophy, and of course, metaphysics.

I called this paper a “scheme” and not a theory for a reason: it’s an incomplete reflection. We will truly be enriched when we understand not just that the universe is a mosaic of interacting systems, but the rules underlying that mosaic. We should aspire to be able to tell the entire story of the universe, from quarks to elementary particles to atoms to molecules and the giant planets and stars made of them, from the chemical reactions, autocatalytic compounds, single-celled and multicellular organisms that may occupy some of those planets, from the adaptive brains of some of those multicellular organisms and their groups, from their economic and political institutions to the stories of their entire civilization, from the music of Beethoven to the art of Banksy, and from the musings of Nietzsche to the calculations of Barabasi.